The assessment process throws up some interesting questions / problems for both tutors and students. Hearing a reading from Joanna Moorhead’s biography of Leonora Carrington on the radio this morning and rereading the Lygia Clark text, that I had saved for Emily, prompted me to think, ‘don’t limit your (our) selves’. Whether it’s in response to the market, marks, or expectations. Reflect on the assessment and absorb, accept, challenge. A course is only an environment and a set of individuals – both students and staff – working it out as they go along.

Well done to everyone for progressing to the next stage – I look forward to exciting masters projects…

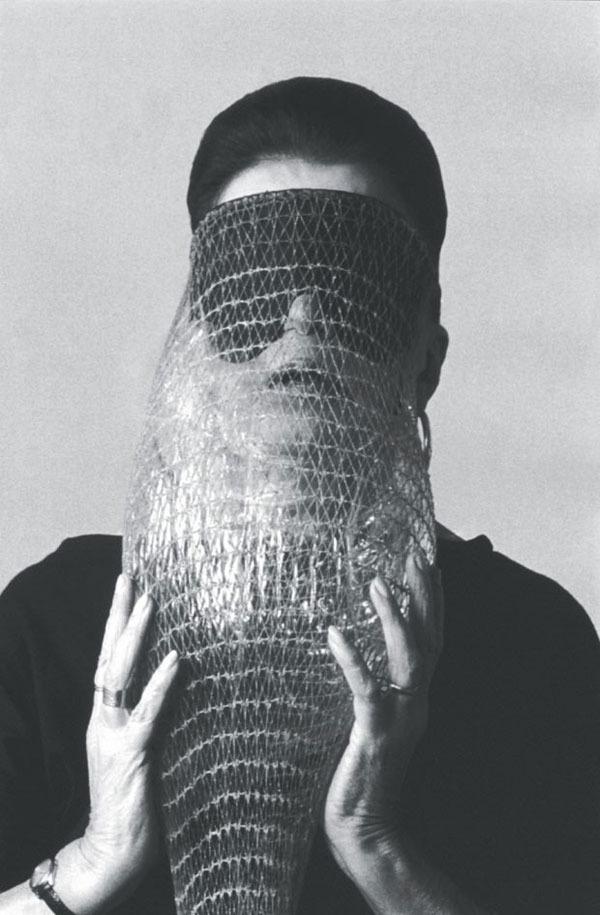

Between 1966 and 1988, a period that coincided with a personal crisis and subsequent long sojourn of exile in Europe, Clark achieved a radical conclusion to the concepts and practices that she had confronted during the 1960s. During this time, she made very simple objects out of ordinary things such as gloves, plastic bags, stones, seashells, water, elastics, and fabric. These “sensorial objects” were designed to make possible a different awareness of our bodies, our perceptual capabilities, and our mental and physical constraints. Clark’s repertoire of sensorial objects, all based on ready-made and transformed everyday tools, was meant to be activated in both contact and coordination with our body and organic functions. By matching our gestures with these simple objects, Clark intended to project an organic dimension over inert and industrial materials.

Ultimately, Clark’s research drove her to profoundly question the status and utility of conventional works of art as means of expression. Claiming to abandon art making, she created a practice using materials applied directly to the body, engaging with her subjects in a very direct way. Among the propositions (as she called them) featured in this last section of the exhibition are works generally considered “biological architectures” and other experiential or “relational objects” from the early 1970s, which are shown here alongside original and replica devices that Clark conceived in order to allow the audience to approach relational experiences. It is only now, after her death, that this last chapter may be read in terms of the histories of happenings, performance, and public engagement as a radical form of art making.

From MOMA press release, published here.

You must be logged in to post a comment.